| Home | Features | Club Nights | Underwater Pics | Feedback | Non-Celebrity Diver | Events | 24 April 2024 |

| Blog | Archive | Medical FAQs | Competitions | Travel Offers | The Crew | Contact Us | MDC | LDC |

|

|

|

ISSUE 18 ARCHIVE - PFO AND DIVINGDr Oli FirthModern life is infested with an unwelcome profusion of TLAs*, leading to potentially excruciating misunderstandings. Medicine has to take its fair share of blame for this. PFO, for example, can relate to:

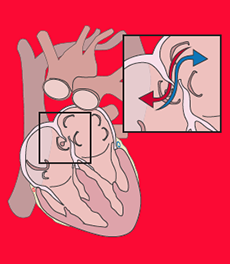

In this article, however, we’ll concentrate on its more widely accepted meaning, that of Patent Foramen Ovale. Classicists will know that a foramen is a hole, and no points for guessing that a PFO is an oval-shaped one that’s still open. This particular aperture lies between the two upper chambers of the heart, the atria (see diagram). The wall between these chambers is called the septum, and hence a PFO is one of a number of so-called Atrial Septal Defects, or ASDs. SFW, I hear you cry. Read on... Human hearts have two different circulation circuits. Deoxygenated blood enters the right atrium and passes to the right ventricle, which pumps it to the lungs to get oxygen. This blood re-enters the heart through the left atrium and passes to the left ventricle where it is pumped to the rest of the body. So the first circulation (the “right heart”) oxygenates blood, and the second (the “left heart”) circulates it to the rest of the body. We don’t, unlike Time Lords, have two hearts, by the way; the right and left heart thing is simply shorthand for which side of the heart we’re referring to. All clear so far? In the womb, the situation is different; our lungs are essentially redundant as they are filled with amniotic fluid, so blood is oxygenated by the placenta. Blood therefore bypasses the right heart (and the lungs) by flowing between the two atria through a PFO, so-called “right to left shunting”. Thus we are all dependent on a PFO before we are born. When the lungs start working at birth, a flap gradually closes this hole so the blood can flow to the lungs to be oxygenated. However, in 25-30% of people, the flap doesn’t fully seal, and can be opened again if the right heart pressure rises above the left. Normally this doesn’t happen: the pressure required to pump blood around the whole body is far greater than that required to get blood to the lungs and back, so the left heart is correspondingly at much higher pressure than the right. However, a surge of venous blood can occasionally cause right heart pressure to exceed left. Typical situations in divers might be soon after an over zealous Valsalva manoeuvre, lifting a tank, or when struggling up a ladder heavily laden with wet kit. Blood then shunts from right to left across the PFO, and if the blood contains nitrogen bubbles, they will be squirted around the body by the left heart, to wreak potential DCS havoc as they lodge in small blood vessels. Although conceptually this is a very convenient mechanism, the data on DCS and PFO suggest the link isn’t quite so simple. One obvious point is that in theory 25-30% of divers have a PFO, but nowhere near this number get bent, so other important factors must be at work – the size of the PFO, bubble load and individual variation in susceptibility will all have an influence. Testing for PFO is therefore usually reserved for those who’ve suffered bends in non- provocative circumstances (florid skin and neurological symptoms in particular), or those who are at high risk (eg. migraine sufferers who regularly dive deep and long). The “bubble study” involves injecting tiny bubbles into a vein and following their passage through the heart using an echo probe. If a PFO is present, bubbles can be seen passing through it. Various types of occluder device can be deployed across a PFO via a catheter introduced into a groin vein, and usually after a few months and another bubble study confirming the PFO is sealed, diving can safely resume. For those with a PFO who don’t want or need closure, safe diving practices to minimise nitrogen load are important. These include avoiding deco dives, keeping bottom times and depths to a minimum, avoiding repetitive dives, and using oxygen-rich breathing mixes. The key point is to remember that a PFO doesn’t cause DCS – bubbles do. So keep them in the beer, where they belong. Although since growing a beard, I’m much more of a real ale man now... *Three Letter Acronyms. TLA is a fine example of an autological word (a word that describes itself). My favourite of these has to be “sesquipedalian”, an adjective meaning “given to using long words”... Previous article « Crocodiles Next article » Eco Chat: UK's Marine Conservation Zones Back to Issue 18 Index |